How ignoring the rules creates a better customer experience: two examples

Front-line staff that interacts with customers are often underpaid and have little authority. In turn, engagement is low, and staff turnover is high. Executives sometimes see them as a cost center that should be measured on efficiency.

I believe this is the wrong approach.

These are the people that are in direct contact with your customers. They’re the first to sense market signals. They can create amazing experiences that build customer loyalty when given the authority.

As a speaker and consultant with an international client base, I often interact with front-line employees while traveling. Here are two stories from my latest trip to the USA.

Example #1: Booking.com call center

Because I would arrive at 11 pm, I booked my first night in an airport hotel. In the days before my trip, I tried to find out what would be the easiest way to get from the airport to the hotel. I read somewhere that there would be a complimentary shuttle, but I wasn’t sure it would run that late, how long I would need to wait, and where I would find it in the terminal. I couldn’t find the information on the hotel’s website. Surprisingly, the site didn’t provide an email address, and I didn’t want to call them because of the international costs.

Since I booked through Booking.com, I tried contacting the hotel through the messaging feature of their app. But I received no response after trying multiple times with days in between.

Before my departure, I decided to call Booking.com’s customer support line.

The phone rang, and a lady picked up with an Indian-sounding accent. I explained the situation. She responded: “I hear you are looking for information on the free hotel shuttle and couldn’t find it. You tried to […], which didn’t resolve your question. I apologize for this situation and completely understand why you would feel frustrated. But there is no need to worry, Mr. Kamer because I am now on the phone with you and will do my best to resolve this situation.”

Wow, I was surprised. This was an exceptional response. Apparently, she was well-trained to respond empathetically. She understood my concern and played it back to me. So far, so good.

“Would you mind if I put you on hold?” Sure.

Ten minutes later, she was back. “I apologize for the long wait Mr. Kamer. I had to consult with my supervisor. Since you are calling the reservations team, I would like to transfer you to our taxi booking team to resolve your question. Would you mind if I put you on hold?”

I responded: “I’m sorry, but that’s not what I want. I want to use the hotel’s complimentary airport shuttle service. I’m surprised you want to transfer me to the taxi booking team so they can sell me a taxi.”

She said she understood and proposed that she would try to contact the hotel and send me a message through the app after she had found out the information. I accepted and hung up. When I arrived at the airport about 20 hours later, there was no sign of any message from Booking.com or the hotel.

I was left wondering:

Why did she need to consult with her supervisor? Did she have to ask for approval to spend the money to call the hotel?

Are they encouraged/incentivized to cross-sell taxi bookings instead of trying to solve my problem?

What happened after we hung up?

I received an automated “How did Jane do?” email. What will happen if I give her a 1-star review? Will it reflect poorly on her record? And is that fair, given it wasn’t her fault, but the system failed?

Let’s contrast this with another interaction I had later that day.

Example #2: Airport lounge cleaner

During my 3-hour layover, I visited the Delta airport lounge. I grabbed a drink and a snack and found myself a comfortable seat to do some work. After some time, a cleaner came to me. He was dressed in a black shirt with a white bow tie.

He asked if he could take my empty bag of crisps. I said yes. Then, he started a conversation. “How are you today?” I responded that I felt jet lagged since my body thought it was 4 am and told me I should be asleep. He asked where I traveled from and where I was heading.

This interaction was a relatively usual chit-chat that you often get in a hospitality setting. Superficial but friendly.

But then something changed.

He continued to ask questions. “Have you ever been to Italy?” I said yes, and then I asked, “Have you? Do you have roots there?” “No sir, I am from Ethiopia. But I got Italian classes at school; I enjoy the language and try to practice whenever possible.”

He asked about other languages I spoke. And which countries in Europe I had yet to visit. This became a fun exercise of memorizing geography, and we went back and forth, coming up with different countries, “And what about… Hungary? Lithuania? Finland?”

Time flew because it was an engaging conversation. Then, I noticed he was scanning the room, perhaps seeing if anybody was watching. He told me he would be right back.

He walked around, picked up a few plates with leftovers, and returned. He asked about my favorite cities. We spoke about Italian food.

I enjoyed feeling connected to a genuinely interested human being. And I noticed he was deviating from the rules while doing it.

All the while, he was wiping clean the table next to me. This was unnecessary because nothing had happened since he last cleaned it while talking to me earlier. Why did he need to act like he was cleaning?

Disobeying the rules

In both cases, systems were in place trying to drive particular behavior. How the agents dealt with the rules made the difference:

In the call center example, she knew that what she would propose was not what I wanted. She abided by the rules she was given.

In the cleaner example, he was bending the rules to create a positive customer experience — and have fun in his job.

Decentralize authority to improve results

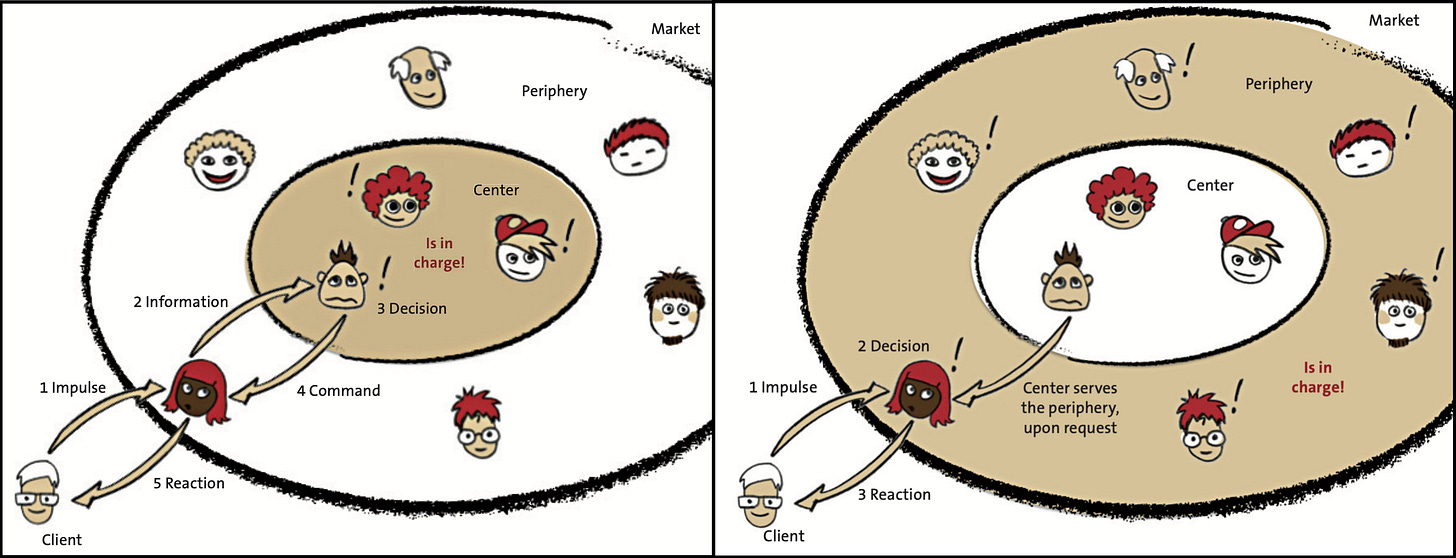

Niels Pflaeging, in his book Organize for Complexity, has made a great visualization of a system without and with decentralized authority:

Here’s my advice if you’re an executive interested in improving customer experience:

Talk to front-line employees, and deepen your understanding of what they face during their day-to-day jobs. Ask them what is in the way for them to do their best work.

Create a feedback loop from the front-line to your strategy to pick up on market signals.

Give your front-line employees decision-making authority to do the right thing. Explicitly allow them to disobey the rules when it makes sense.