Four strategy habits of high-performing leadership teams

A strategy should help focus the organization’s energy in a certain direction. But it is often done poorly

A strategy should help focus the organization’s energy in a certain direction. But it is often done poorly: the strategy is created in isolation, is not connected to the reality on the ground, outcomes are fluffy, and we use the wrong metrics. Read on to learn how to turn that around.

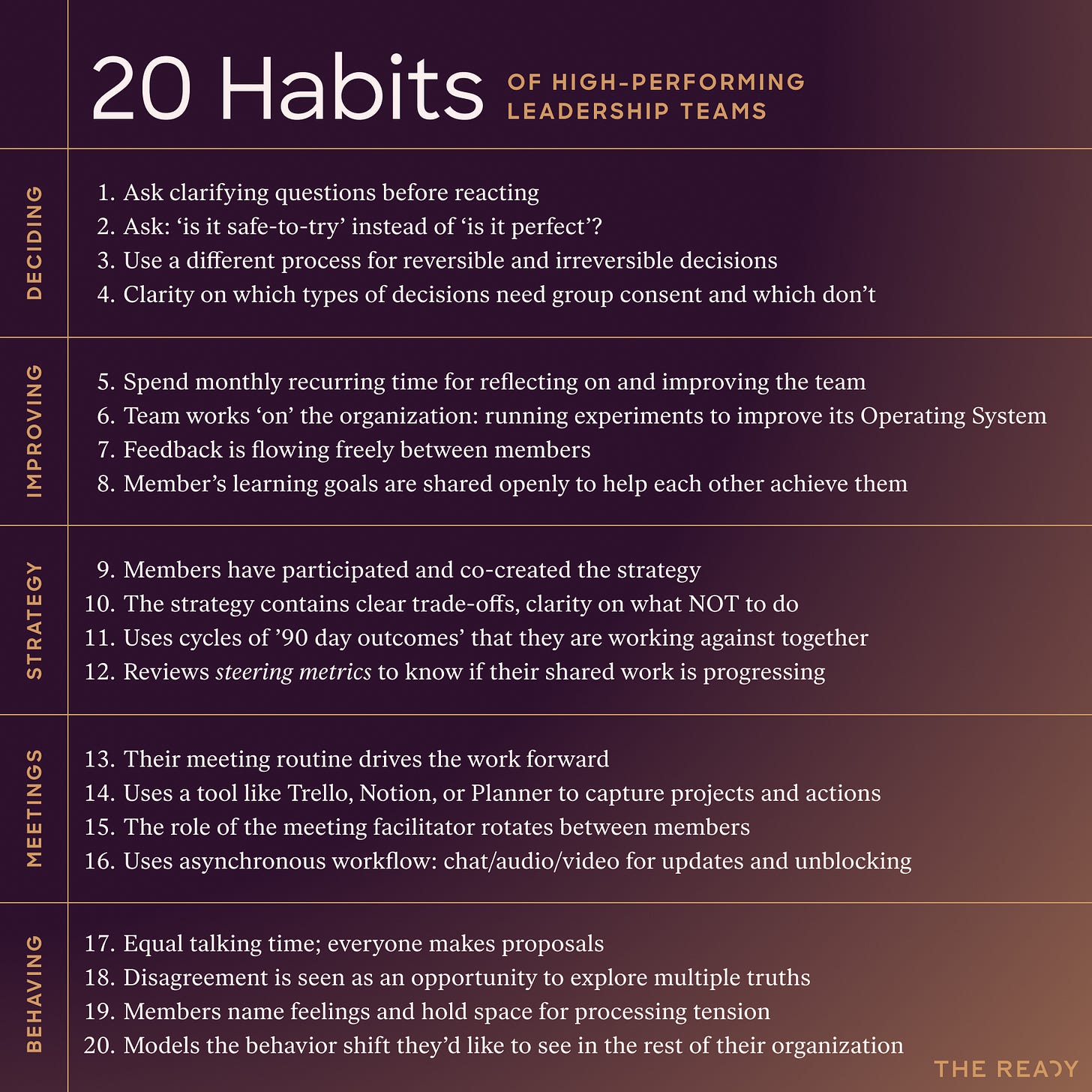

This month, I’m covering the 20 habits of high-performing leadership teams. Last week I covered improvement habits. This week is all about the strategy habits I’ve observed in the best leadership teams:

#9 Members have participated and co-created the strategy

In his book Good Strategy, Bad Strategy, Richard Rumelt describes the ‘kernel’ of a good strategy (image by Gudjon):

Creating a good strategy involves ‘mapping the territory’ by diagnosing obstacles and opportunities and then creating guiding policies. Because the environment is complex, getting as many different perspectives as possible is key.

Invite a cross-section of the organization to co-create your strategy. This ensures that you'll develop a strategy rooted in the reality on the ground.

Even better, invite customers and stakeholders from outside the organization to offer their views.

Leveraging the wisdom of the crowd will increase your chances of finding a strategy that works and can be executed.

#10 The strategy contains clear trade-offs, clarity on what NOT to do

Saying YES to something should mean you're saying NO to something else. Otherwise, your list of priorities will stay a 'wish list' nothing more than 'wishful thinking.'

It’s not uncommon for leaders to claim they can neither deprioritize anything nor make trade-offs. Behind this thinking is the flawed premise that trade-offs aren’t happening in the first place. However, trade-offs are always happening whether you notice them or not.

Your power lies in choosing your trade-offs consciously. If you don’t choose your own trade-offs, the world around you will decide them for you.

It is easy to make a list and say ‘yes.’ But the reality is, when those priorities make contact with the teams that need to execute them, it often falls flat. Why? Because having a list doesn't provide the necessary context to make the more granular decisions that need to be made along the way. The list is often too long and doesn't tell me what NOT to do.

When making a priority list, you’re making trade-offs. You’re making decisions about what you won’t do. At The Ready, we've found 'even over statements' a very helpful practice to make trade-offs explicit, facilitating high-quality local decision-making. Here are a few examples:

Exclusive product line *even over* Mass market adoption

Amazing customer service *even over* New product features

Mobile experience *even over* Desktop experience

Revenue growth *even over* User growth

The recipe:

[One good thing] even over [another good thing].

And the statement, when reversed, should still make sense.

Read more about Even Over Statements.

#11 Use cycles of ‘90 day outcomes’ that they are working against together

To get started, sit down with your team and co-create answers to the following questions.

If a longer-term perspective is missing, start with:

What does it look like when we are wildly successful?

What end state would make us inspired and proud?

What outcomes must we achieve in 1-3 years to bring our purpose to life?

Given that longer-term vision, reflect on what needs to happen next.

If we are wildly successful in the next 90 days...

What will be different about our product / this team / our department?

What will be different about our relationships with our customers and stakeholders?

What do we want to have completed at the end of the next 90 days?

Making a 'wish list' is easy, but to really make it work, write the outcomes using the outcome-oriented language—more on how to do this well in this LinkedIn post.

#12 Review steering metrics to know if their shared work is progressing

Leaders love measuring things. I've often sat in board meetings where pages and pages of KPIs were reviewed, leading to critical questions.

It feels good to keep an overview. However, it gives a *false* sense of being in control.

Many KPIs are *lagging* indicators: meaning they can't be influenced *directly* and they don't help us take action.

The best leadership teams focus their time and energy on only a few metrics that qualify as *steering* metrics.

A good steering metric:

📈 is a *leading* indicator of success

🏌️♂️ helps you to take action and make better informed decisions

⏰ is time-bound (ie. x per month)

Most leaders care about revenue. But we can't influence that directly. So, what leads to revenue?

Amount of paying customers. But we can't influence that directly. So, what leads to paying customers? Many different things.

Imagine you're running a webshop. Depending on what your team is responsible for, you might want to track the following:

Amount of people visiting our webshop <= influenced by social media or ad campaigns

Conversion rate of online funnel <= influenced by optimizing the site

Newsletter subscribers <= influenced by experiments to get more signups

Don't overthink it:

start simple, track 3-5 metrics

qualitative metrics are okay

learn by doing, inspect and adapt

i.e. treat steering metrics as a hypothesis of what might drive a desired lagging outcome

🚨 Roundtables for future-oriented leaders

Are you leading a team, or are you a member of a leadership team? Then I’d like to invite you to our leadership roundtables. Register here to get invited to our session on "reinventing strategy" in September.

In this newsletter, I’ve covered habits #9-#12. Stay tuned for #13-#20! Next time: meeting habits.